One of the p.r. (public relations) stories in Buddhism, a story that always resonated with me, is the tale of the youthful and cosseted Siddhartha taking a chariot ride outside his protective palace walls. At birth, it had been predicted that Siddhartha would become a great king or a great wise man, and Siddhartha's father was keen to have his son grow up and be a king: Wise men were a dime a dozen.

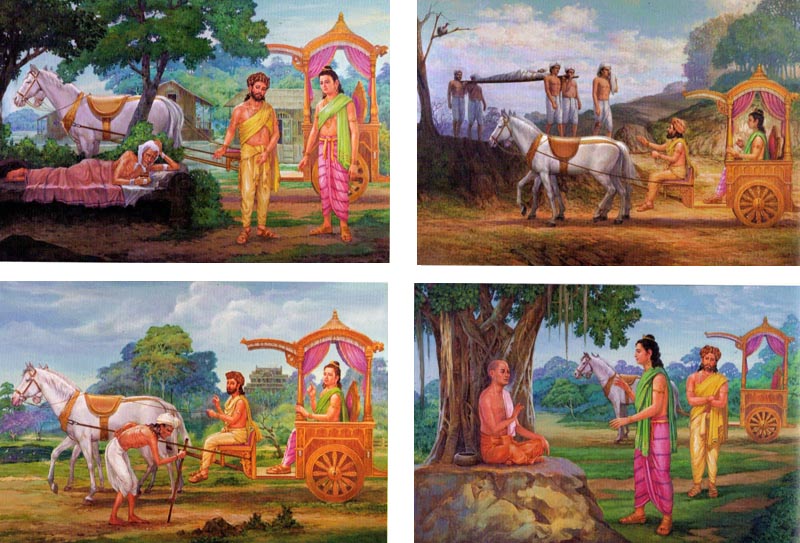

So Siddhartha's father built a magnificent palace for his son, a lavish and well-provisioned place ... full of wine, women, song and a safe haven. But on four occasions, the young man was chauffeured out beyond the palace walls and it was outside those walls that dad's plans came undone. On each of those occasions, Siddhartha saw things that troubled him because inside the walls, such things were kept hiddenc. He saw an old person; he saw a sick person; he saw a dead person; and he saw a monk or sadhu. In each instance, it was the charioteer who had to explain to the well-protected prince what he was looking at.

OK, the punch line was inevitable. At 29, the prince left the palace walls behind and began his search for peaceful answers to war-like questions: Why do people get old, get sick, die? Where was the peace imputed to such people as monks or sadhus? And at 35, after really busting his chops, he attained what others refer to as success ... an understanding that he then spent the rest of his life expounding to others. He was the Buddha, the one who was awake ... and Buddhism was born ... and the p.r. was set in motion.

It's pretty good p.r., in one sense. Who -- what individual man or woman -- does not entertain the questions Siddhartha asked? Who does not feel the frisson that waning capacities or illness or death can instill? It's out-of-your-control stuff and not being in control is spooky ... factual as a dandelion but spooky nonetheless. Who does not leave the palace of life-until-now without a sense of foreboding? Facts may insist, but who knows if the adventure will end in what others call success ... or, more important, what I call success?

It's good p.r. because it relates to what is human. Some religions use that p.r. to build their spires ever higher, trading on the fears of the multitude and gathering power and wealth. But even setting such charlatanism aside, still it's pretty good p.r. because at least it can put a fire under an uncertain heart -- let's get down to brass tacks! I want the peace imputed to the sadhu or monk, the one who seems capable of strolling through old age, sickness and death (or a host of other concerns) without a quiver. I too would like to have a bright light in what may seem to be a dark place.

OK. Each travels according to his own p.r.

But today, I am taken by the charioteer ... the taxi driver who had to explain the facts of life to the well-heeled and in-control passenger. He knew how to drive and he knew what was what. Did he have some deep understanding that would later be imputed to the Buddha? Did he quiver and wish that he too could be as kool as a monk or sadhu? Or did he understand that quivering was not so bad ... that life was life and ... well ... driving was his business. Did he live within the palace walls or have a house in the suburbs? What did he know and in what way did he know it?

I'll never know what the charioteer knew any more than I will ever know what the Buddha knew. But what they knew is their business, their p.r. Their p.r. dribbles down to me and infuses my own p.r.

Public relations is not a bad thing, but anyone in their right mind would have to concede that p.r. is constructed and confected as a means of promoting or pointing out something else. The four-color advertisement for a Chevy relates to something that actually is a Chevy. Something else.

And what else is there? What is it like when p.r. no longer has a something else to point to?

I like the charioteer. He seems to have been a pretty good driver ... just like the Buddha ... just like you.

No comments:

Post a Comment